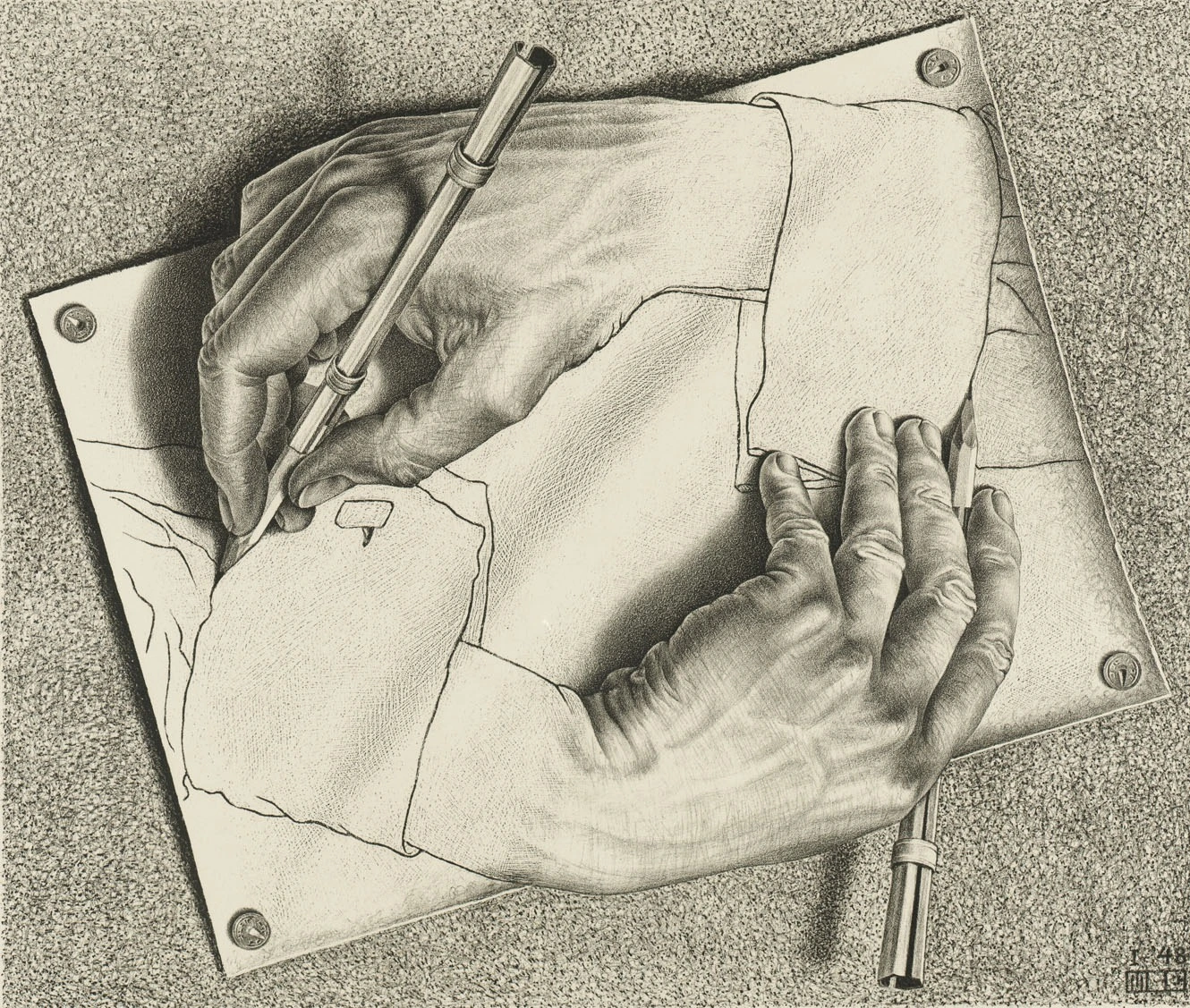

Billions are spent on “digital transformation” each year. Many efforts struggle—not just because of bad tech, but because teams dismantle fences no one stopped to understand.

The paradox of progress

In 1929, G.K. Chesterton articulated a principle worth revisiting:

“There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

This isn’t about blindly preserving the past. It’s about recognizing that many systems—however odd they appear—were someone’s solution to a real problem.

Often, the problem outlives the memory of why we solved it.

The architect’s dilemma

Walk through any enterprise codebase and you’ll find them—the fences. That convoluted authentication system. The seemingly redundant validation. The multi-approval workflow for what looks like a minor change.

Our instinct is often demolition. These barriers slow us down, complicate architecture, challenge our sense of elegance.

But much of what seems like unnecessary complexity might be what’s left behind after a system made it through something hard.

That unusual validation rule? It might be protecting against a regulatory issue. The multiple approvals? Perhaps they prevent the kind of mistake that once caused serious problems.

The fence-builders may be gone. But their hard-won lessons often remain—quietly encoded in the structures they left behind.

Innovation theater

We’ve developed certain myths around disruption.

“Move fast and break things” can work—until one of those things turns out to be essential.

Many failed modernization projects share a pattern:

- New team inherits a “legacy” system

- It looks unnecessarily complex

- Team rebuilds with modern simplicity

- Edge cases resurface

- Patches accumulate

- New system grows complex too

- And the cycle repeats

Each generation tends to believe it sees more clearly. That previous architects were working with inferior tools or knowledge.

Sometimes that’s true. Often, it’s just distance from the original context.

The cost of forgetting

Imagine a team spending $2 million to rebuild an “outdated” inventory system. The old system has strange rules: no moves on Tuesdays, paper trails for certain transfers, manual review triggers that seem random.

“Archaic nonsense,” the team says. The new system is faster, cleaner, more modern.

Then come the consequences.

Those “strange rules”? Court-mandated procedures from a legal settlement. The Tuesday restriction? Part of a labor agreement. The paper trails? Required for controlled substances.

The original devs have moved on. Documentation is sparse. But the fences had quietly protected the company—until they didn’t.

Working with fences

This doesn’t mean we should preserve everything. Stagnation has its own risks.

But thoughtful innovation might start differently.

First, investigation.

Before changing anything, try to understand it. What problem might this be solving? Talk to long-tenured people. Dig into commit logs, old tickets. If the reason isn’t obvious, it might be buried—not absent.

Second, context.

That messy system was likely built by capable people navigating real constraints—regulatory, budgetary, organizational. The system often tells a story—if we’re willing to listen.

Third, documentation.

If you do remove a fence, record its purpose and why it seemed safe to remove. Future architects deserve more than silence where structure once stood.

The harder path

Quick changes feel like progress. They make great presentations.

Understanding takes more time. It requires humility—accepting that previous builders might have known things we don’t.

It needs patience—investigating before acting.

It calls for judgment—recognizing that some constraints serve important purposes.

But here’s what Chesterton understood: the fence we don’t understand might be the one we need.

In our eagerness to build the future, we sometimes risk dismantling the foundations that could support it.

The next time you encounter a fence—a process that seems pointless, a system that appears obsolete, a rule that feels arbitrary—pause.

Consider:

What might I not be seeing?

What problem could this be solving?

What lesson might be encoded here?

If you can’t explain why the fence exists, it may not be time to tear it down.

Leave a comment