Every organization believes it designs its systems deliberately. Architecture diagrams are drawn, interfaces are defined, boundaries are established. But there’s an uncomfortable truth lurking beneath these careful plans: the real architecture was decided long before the first line of code was written. It was determined the moment teams were formed.

The invisible architect

In 1967, computer scientist Melvin Conway observed something that should have been obvious but wasn’t: organizations produce systems that mirror their own communication structures. Not sometimes. Not usually. Always.

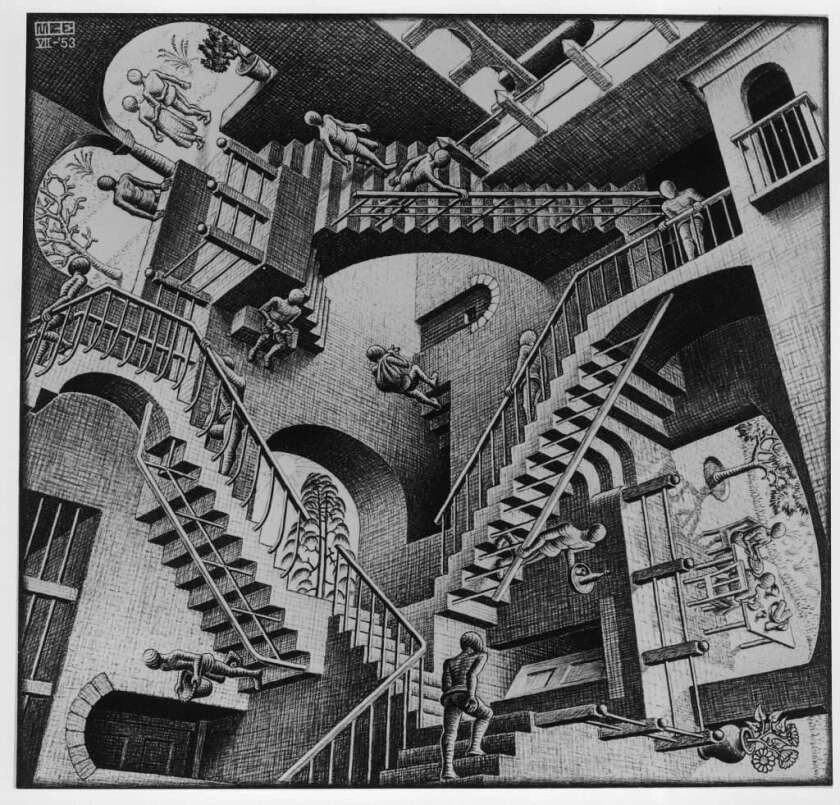

This isn’t a tendency or a pattern—it’s closer to physics. Systems reflect the teams that build them with the same inevitability that water flows downhill.

The principle is deceptively simple: if you have four teams working on a compiler, you’ll get a four-pass compiler. If your frontend and backend teams rarely talk, you’ll get a system with a rigid, painful interface between them. If your organization prizes individual ownership over collaboration, you’ll get a collection of personal kingdoms masquerading as a unified system.

Conway didn’t discover this by studying successful projects. He noticed it in the failures—the places where brilliant engineers built exactly what their organization structure demanded, not what the problem required.

Backwards by design

Most companies approach system design backwards. They draw the ideal architecture, assign teams to build it, then wonder why reality refuses to match the blueprint. They blame complexity, changing requirements, or technical debt. Rarely do they question whether their beautiful design was ever possible given how their teams were organized.

Consider the typical enterprise: separate teams for database, backend, frontend, and operations. Each optimizes for different goals—data integrity, business logic, user experience, and stability. What emerges isn’t a system but a negotiated settlement. Interfaces become diplomatic boundaries. Integration points turn into contested territories.

This isn’t a failure of engineering. It’s Conway’s Law in action. The teams built exactly what their structure allowed them to build: isolated components held together by treaties instead of trust.

Fossil records

The most insidious part of Conway’s Law is its invisibility. Teams don’t consciously decide to mirror their organization—it happens through countless small decisions.

A feature requires coordination between two teams. But scheduling is hard, so they define an API instead. That API calcifies into a permanent boundary. Another team needs data but builds their own store to avoid the politics. The system fragments, one reasonable decision at a time.

Each choice makes local sense. Together, they create global dysfunction. The architecture becomes a fossil record of every communication failure, every unresolved tension.

Remote work has amplified this. Physical distance becomes system distance. Time zones become asynchronous interfaces. The casual conversations that might have prevented architectural drift never happen. The system sprawls, guided by organizational structure rather than design.

Wielding the law

Here’s where most discussions of Conway’s Law go wrong: they treat it as a problem to solve. But you can’t solve gravity. You can only work with it or against it.

The organizations that thrive don’t fight Conway’s Law—they embrace it. They recognize a fundamental truth: if system architecture will mirror team structure anyway, why not design teams to create the architecture you want?

This isn’t about reorg theater or musical chairs with reporting lines. It’s about intentional alignment. Want a modular system? Create autonomous teams with clear boundaries. Need tight integration? Put those people in the same room—physically or virtually. Trying to build a platform? Make sure your platform team actually talks to the teams who’ll use it.

But this requires something most organizations struggle with: admitting that their current structure might be wrong. It’s easier to blame the technology, the requirements, or the last vendor than to acknowledge that the org chart might be the problem.

The practical paradox

Some try to bypass Conway’s Law through process—architectural review boards, collaboration tools, DevOps methodologies. These efforts don’t fail because they’re bad ideas. They fail because they’re fighting physics with philosophy. No amount of process can make two teams who don’t trust each other build a well-integrated system.

The law is inescapable because it reflects something deeper than software: human nature. We communicate with those close to us. We trust those we know. We optimize for our local context. Our systems, being human creations, embody these same patterns.

Conway’s Law isn’t a management problem or a technical challenge. It’s a force of nature in the world of human systems. The wise approach isn’t resistance but alignment. Design your teams for the architecture you want, not the one you have. Accept that changing systems means changing organizations. Recognize that every reorg is an architectural decision, whether you admit it or not.

Most importantly, stop pretending that architecture is a purely technical concern. Every system design is also an organizational design. Every architectural decision is also a social one. The sooner we accept this, the sooner we can stop being surprised when our systems look exactly like our org charts.

Perhaps Conway’s greatest insight wasn’t about software at all. It was about the impossibility of separating human systems from the humans who build them.

Leave a comment